On Naming

“A proper name, when one meets with it for the first time, is existentially connected with some percept or other equivalent individual knowledge of the individual it names. It is then, and then only, a genuine Index. The next time one meets with it, one regards it as an Icon of that Index. The habitual acquaintance with it having been acquired, it becomes a Symbol whose Interpretant represents it as an Icon of an Index of the Individual named.”

(C. S. Peirce. Speculative Grammar: Propositions.)

Notes from Michael Ohl’s book, “The Art of Naming” (translated by E. Lauffer, published by MIT Press).

Prologue: The Beauty of Names

- “Each one [creature] has a name, … and it is through naming that it becomes part of our perception of nature.” Problem: How may changing nomenclature for natural beings indicate a change in “our” perception of nature?

- “A species name conveys authority and knowledge, structuring the living world according to science. A scientific name is therefore a culminating point of a range of impressions, knowledge and interpretations.”

Hitler and the Fledermaus

- The German words for the shrew and the bat are Spitzmaus and Fledermaus. These are both compound words formed by joining substantives. The second element, “maus”, is the base or the determinatum and “determines both the denotation and the grammatical gender of the compound.” The first element is the determinative or determinant, which may be multiple words, more precisely qualifies the base. Example in English: mockingbird.

- The task of systematic biology: find invariants that can most reliably group related creature together.

- Since appearance may be insufficient, use anatomical features of the skull and/or teeth. This has the added advantage of being able to incorporate fossils.

- “Groups of species are described as ‘natural’ when evidence exists of an ancestor common only to them; systems of organisms comprised solely of such groups are designated in the same way. These stand in contrast to artificial groups and artificial systems, in which the species’ linkage is based on congruities that can be shown not to have emerged from a unique evolutionary change in the most recent common ancestor.”

- The classification of creatures, say from Aristotle to Linnaeus to current international organizations, have progressed from relying on animal behavior to anatomical dissection to anatomical imaging and now genetics.

- A taxonomic problem: “The arthropods, [spiders, insects, crabs] with their rigid exoskeleton and eponymous multijointed appendages, are closely related to velvet worms and water bears, two groups of soft-skinned organisms with simple, inarticulate legs that don’t seem arthropodic in nature.

- Campbell, L. I., Rota-Stabelli, O., Edgecombe, G. D., Marchioro, T., Longhorn, S. J., Telford, M., J., … Pisani, D. (2011). MicroRNAs and phylogenomics resolve the relationship of Tardigrada and suggest that velvet worms are the sister group of Arthropoda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 108: 15920-15924.

- A new old animal

- Two possible solutions:

- “Velvet worms and water bears are thrown in with the arthropods, thus expanding the semantic field of Arthropoda.” Cost: the “old” arthropods will require a new name.

- “The old arthropods stay arthropods but acquire a new superordinate name, along with the velvet worms and the water bears.”

- The cost of updating knowledge (documentation, pedagogy) seems tacit here, and so remains unqualified.

- Since the first solution was adopted by the systematic biology community, the new name was formed by placing eu- (Greek prefix, indicating normal, typical, good, beautiful) in front of the old Arthropoda, hence Euarthropoda.

- How is knowledge organized and created?

- International Code of Zoological Nomenclature documents the rules of naming.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature edits the rules.

- Some important classical texts in naming:

- Friedrich Kluge. Etymological Lexicon of the German Language.

- Helmut Carl. German Plant and Animal Names: Explanation and Linguistic Order.

- Hugo Palander. Old High German Animal Names, Volume 1: The Names of Mammals. 1899.

- Hugo Suolhati. German Bird Names: A Linguistic Study. 1909.

- Theodore of Canterbury. Leviticus Apostils. ~700.

- An example of etymology:

- Pferd, horse -> pfarifit (Old High German) -> pferfrit, pharit, pfert (Middle High German) … -> paraveredus (Medieval Latin) … -> gorwydd (Welsh) -> reda (Celtic)

- How were the linguistic creations reached for the animal names in use today?

- Onomatopoeia: “the mimicry of sounds plays the biggest role in the animal names that have arisen this way.”

- Examples: cuckoo, chickadee, towhee, bobwhite, bobolink, whip-poor-will, Chuck-will’s-widow.

- “Mowe (seagull) is believed to be derived from the Middle High German verb mawen and the Modern Dutch mauwen, both of which signify the meowing of a cat, meaning that an onomatopoeic term has been transferred from one animal to another.”

- Loanwords: brought from an animal’s place of origin into English

- Examples: axolotl (Mexico), jaguar (South American indigenous), jackal (India), impala (Zulu), iguana (Arawak), salamander (Persian), cassowary (kasuari: Malay).

- Recombining old words: “base word is qualified through the inclusion of certain features, such as geographical origin or special physical traits.”

- Examples: Kompassqualle, Wasserspitmaus, Australian snubfin dolphon, Burrunan dolphin.

- Onomatopoeia: “the mimicry of sounds plays the biggest role in the animal names that have arisen this way.”

- Example of folk etymology or reanalysis:

- crevise (Old French) -> ecrevisse (Modern French) -> crayfish (English) -> craw(l)fish (Louisiana)

- Some important modern texts in naming:

- National Audobon Society Field Guides.

- Bernhard Grzimek. Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia. 1967.

- Mammals of Africa.

- Birds of the World: Recommended English Names. 2006.

- A Thesaurus of Bird Names: Etymology of European Lexis Through Paradigms. 1998.

- Grzimek’s three important linguistic directives for popular presentation of scientific content:

- Foreign or technical expressions are to be avoided, or at least reworded using more familiar terms.

- Words that may carry a negative or pejorative connotation are to be replaced with corresponding terms used for humans.

- All the vertebrates, at least, are to have a vernacular name.

- The creation of common names for mammals is not governed by any central rulebooks, and so adoption may vary. Birds are an exception since there’s been literature on birds since antiquity, and ornithologists - amateur or not - are well-organized. E.g. the Standing Committee on English Names is responsible for the official list of English bird names. The International Ornithological Congress (IOC) provides a regularly updated catalog of standard English names on www.worldbirdnames.org

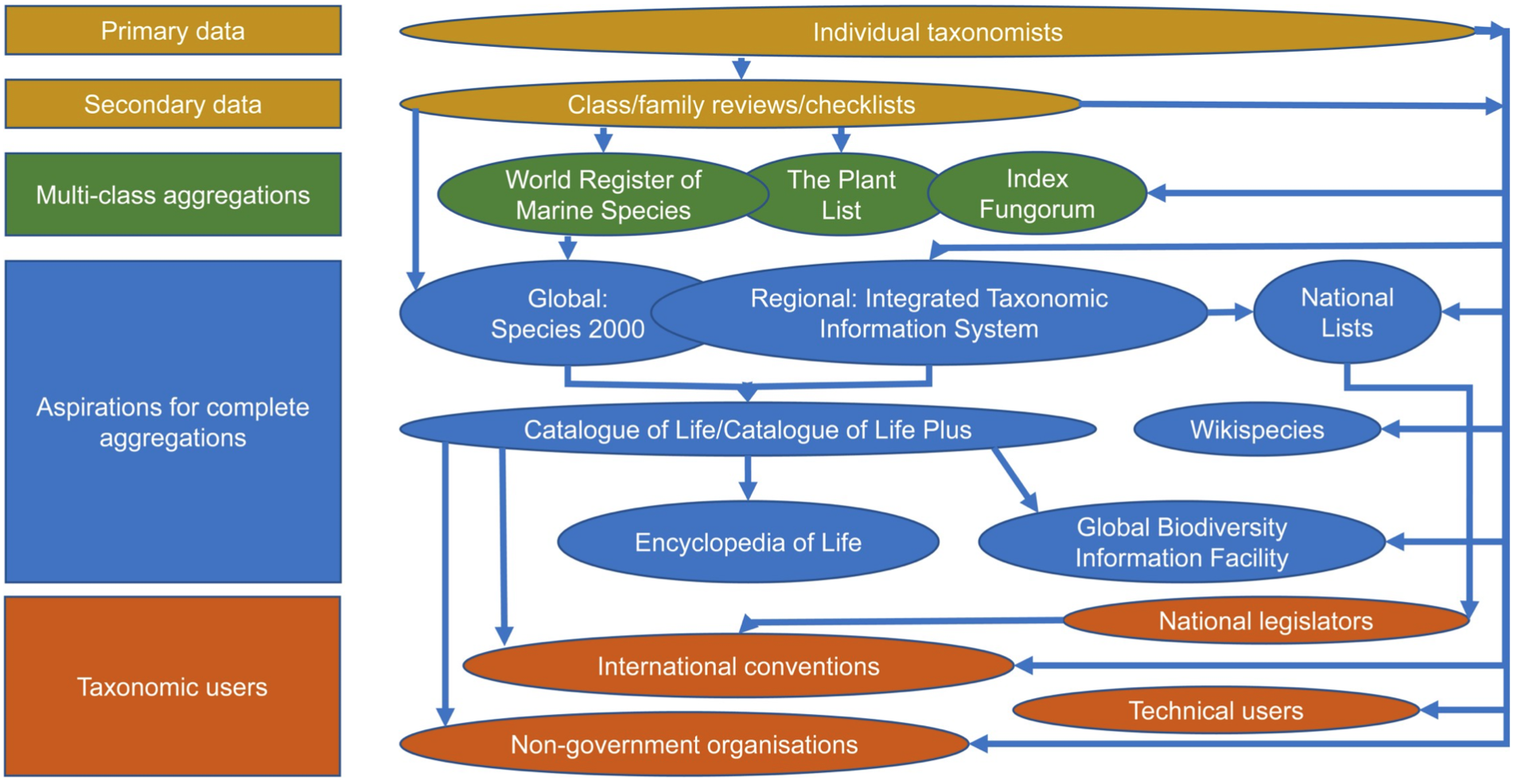

- The issue of nomenclature governance became prominent recently [4], leading to the publication of “Principles for creating a single authoritative list of the world’s species” [5]. The opinion paper uses the following figure to describe the existing process for gathering taxonomic information, and highlight the challenges of decentralized information aggregation. “Thus, whilst there is already a high degree of collaboration among aggregators, with much sharing of lists (Fig 1), all the aggregators remain distinct entities. This results in differences among the lists they propagate, not least because they are updated at different rates. Added to this are the complications that arise when taxonomic groups have multiple authoritative lists.” The principles are:

- the species list must be based on science and free from nontaxonomic considerations and interference,

- governance of the species list must aim for community support and use,

- all decisions about list composition must be transparent,

- the governance of validated lists of species is separate from the governance of the names of taxa,

- governance of lists of accepted species must not constrain academic freedom,

- the set of criteria considered sufficient to recognise species boundaries may appropriately vary between different taxonomic groups but should be consistent when possible,

- a global list must balance conflicting needs for currency and stability by having archived versions,

- contributors need appropriate recognition,

- list content should be traceable, and

- a global listing process needs both to encompass global diversity and to accommodate local knowledge of that diversity.

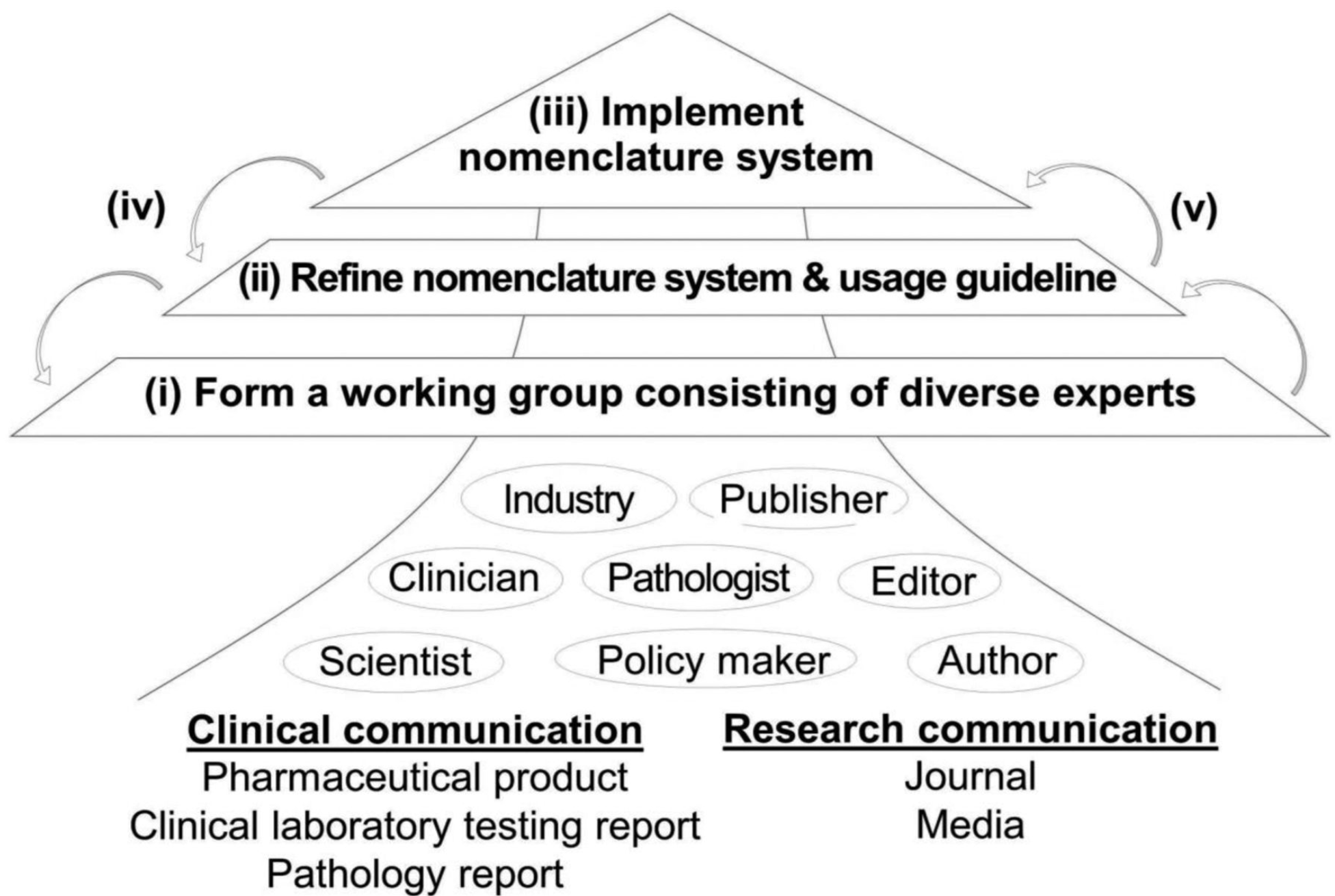

- Other branches of science face similar issues. From [7]:

- The prevalence of function, appearance, and place (locale/geography) in naming: “However, current protein naming systems based on different aspects of structure, function, and cellular localization readily conflict, and they may make less sense if new functions, alternative structures, or novel cellular localizations are discovered.”

- The organization of discourse: “Steps to implement an advanced gene product nomenclature system:

- form a working group consisting of experts from diverse fields,

- develop a standardized nomenclature system and usage guidelines,

- implement the system,

- receive feedback, and

- improve the standardized nomenclature system and usage guidelines.”

How Species Get Their Names

- Two constraints for new species: correctness of genus, uniqueness of species. Three ways to achieve this:

- Scour taxonomic literature for similar creatures e.g. Biodiversity Heritage Library,

- Examine the “type specimen”, i.e. individual creatures that serve(d) as basis for species name,

- The individual type specimen is also called the “holotype”; others, “paratype”

- Examine the “unidentified material” to be able to discern between intra- and inter-species variability.

- Name availability and validity:

- The name must use the Latin alphabet though the description may be in any language and script.

- The name should be traceable to a specific language.

- The name must be a binomial, and the generic and species name must both have at least two characters.

- “A species name usually falls into one of the following word groups:

- An adjective or participle in the nominative singular case. Most species name belong to this group: Echinus esculentus, the edible sea urchin, and the Somatochlora metallica, the brilliant emerald, a dragonfly.

- A noun in the nominative singular case that is in apposition to the genus name: Cercopithecus diana, or Diana monkey.

- A noun in the genitive case: Myotis daubentonii, Daubenton’s bat, and Diplolepis rosae, the rose bedeguar gall.”

- Books on name composition:

- F. C. Werner. Wortelemente lateinisch-griechischer Fachausdrücke in den biologischen Wissenschaften. 1968.

- F. C. Werner. Die Benennung der Organismen und Organe nach Größe, Form, Farbe und anderen Merkmalen. 1970.

- R. W. Brown. Composition of Scientific Words. 1927.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. The Code.

- Principle of priority: “A taxon’s oldest name is always the valid one.”

- Synonymy: different name gives to the same taxon

- Subjective synonymy: different descriptions exist for the same taxon because of different opinions

- Objective synonymy: “two different descriptions exist for the same source material.”

- Homonymy: same name for different species

- Primary homonymy: “a name that was originally described in a genus that already contained the given species name.”

- Secondary homonymy: “the species in question is later moved into a different genus that it was originally ascribed.”

- Example:

- Crabro sabulosus, (J. C. Fabricius, 1787) was suggested be moved to genus Spex but Sphex sabulosus was taken.

- Two secondary homonyms suggested: Sphex ruficornis (1789) and Sphex crabronea (1791).

- Turns out that it actually belongs to the genus Mellinus, so Mellinus sabulosus?

- The Code through proscribes junior homonyms introduced before 1961, so no sabulosus.

- Next in line of succession is Sphex ruficornis: also a junior primary homonym.

- Next after is Sphex crabronea, which after genus and grammatical-gender correction, became Mellinus craboneus (Thunberg, 1791).

- Note that the two constraints - priority, and preservation of name-author association - in this case led of the erasure of the name of the discoverer.

- Synonymy: different name gives to the same taxon

Words, Proper Names, Individuals

- What are the functions of species name?

- Help make scientific communication - data, results, interpretations - clearer.

- Proper names vs appellatives (common nouns):

- “It is … expected that each zoological name will refer unambiguously and unmistakeably to exactly one taxon - that is, one named group of animals such as species.”

- “[N]ames perform their referential function immediately - that is, directly and without a ‘detour’ through semantic meaning… Appellatives help make reference, not to a single thing, but to a whole class of things.”

- “In this one-to-one relationship between name and object, proper names differ fundamentally from appellatives, which refer to a class of objects.”

- Interesting example: Tamias minimus is a proper name but “least chipmunk” is an appellative though they refer to the same object. Since the object is necessarily a class of specific individuals, it makes more sense to say that species, though a class, function as individuals in biological nomenclature i.e. taxons, as classes, are composed of species, and species are a fundamental unit.

- Do species as classes have real or nominal existence?

- Reproductive isolation, or barriers, foster consistent similarities and differences between individual bound together by sexual procreation. (Ernst Mayr).

- How can this be extended to organisms that procreate through “budding” (like polyps) or parthogenesis (like walking sticks)?

- “One important quality of a class is also its consistency, which can be attributed to the fact that a specific, unalterable quality - … essense - is unique to it.”

- Typological species concept: “The notion of species as classes with constant, class-specific qualities represents a monumental contradiction to the notion of a dynamic evolutionary process and changing species.”

- “Contradiction” seems exaggerated, since it is clearly possible to evolve and yet possess similarities and differences that may be consistent over some period of time.

- Michael T. Ghiselin. A Radical Solution to the Species Problem. 1974.

- To be an individual, a “thing”, species should be:

- Spatially and temporally locatable

- “The discontinuity of an ‘individual’ that exists in areas distant from one another definitely poses a problem…”

- Accessible to the senses

- Not directly really, until unless it’s the last individual of a species.

- Be “particular”, and “change”

- Species are particular, and change while remaining the same species (anagenesis).

- Have contingent existence

- Species, as products of evolution, don’t have a necessary existence.

- Spatially and temporally locatable

- “[S]pecies naming is ‘biologically neutral’”:

- Nomenclature, organization of names and naming, is distinct from taxonomy, the codification of biological entities.

- “The objects of the Code are to promote stability and universality in the scientific names of animals and to ensure that the name of each taxon is unique and distinct. All its provisions and recommendations are subservient to those ends and none restricts the freedom of taxonomic though or actions.”

- Reproductive isolation, or barriers, foster consistent similarities and differences between individual bound together by sexual procreation. (Ernst Mayr).

- It may not be obvious, but humans programming computers to human names habitually make assumptions about naming conventions, which are often untrue. Some examples for such assumptions from [11], which also indicate the problems that formality of The Code tries to circumvent:

- People have exactly one canonical full name.

- People have exactly one full name which they go by.

- People have, at this point in time, exactly one canonical full name.

- People’s first names and last names are, by necessity, different.

- People have last names, family names, or anything else which is shared by folks recognized as their relatives.

- People’s names are almost globally unique.

- People’s names are assigned at birth.

- Two different systems containing data about the same person will use the same name for that person.

- People have names.

References

- P. F. Stevens. An Essay on Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science. link

- Ivonne J. Garzón-Orduña. Systematic Biology, Volume 59, Issue 2, March 2010, Pages 242–243. link

- A. J. Drummond. Inferring phylogenies: an instant classic. link

- How a scientific spat over how to name species turned into a big plus for nature link

- S. T. Garnett et al. Principles for creating a single authoritative list of the world’s species link

- T. F. Steussy. Challenges facing systematic biology. link

- Opinion: Standardizing gene product nomenclature — a call to action. link

- DNA barcoding and taxonomy: dark taxa and dark texts/ link

- https://inquisitivebiologist.com/2018/08/24/book-review-the-art-of-naming/

- R. A. Richards. The Species Problem: A Philosophical Analysis

- P. Mckenzie. Falsehoods Programmers Believe About Names. June, 2010. link

Shaohong Feng et al. Dense sampling of bird diversity increases power of comparative genomics, Nature (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2873-9. link